What is a burqa?

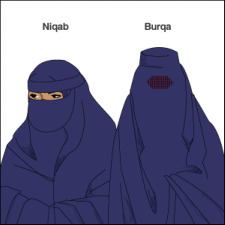

The name varies according to country, custom, and time: burqa, niqab, veil, chadari, abaya: effectively it is a one-person mobile tent with either an opening for the eyes or a lighter fabric to let the woman inside see through.

The name varies according to country, custom, and time: burqa, niqab, veil, chadari, abaya: effectively it is a one-person mobile tent with either an opening for the eyes or a lighter fabric to let the woman inside see through.

In countries where the burqa is required by law or imposed by male violence and female policing of the woman’s “honour”, adult women sometimes suffer from Vitamin D deficiencies because their skin may never get direct sunlight.

There is no requirement in the Qu’ran for Islamic women to cover their faces or to tent themselves with fabric in a burqa or chadoor.

The Islamic requirement that does exist, that believing men and women should dress and behave modestly, is culturally applied to women, and this double standard has been discussed at length by Muslims and non-Muslims. (I’d note that neither Islam nor any other religion nor the secularist community is unique in having double standards of behaviour and requiring women to behave to standard or face cultural punishment.)

But the Quran does address the matter of veiling in such a way that it has been interpreted historically, if not necessarily correctly, by Muslim clerics as applying to women.

The veiling of women was not an Islamic innovation but a Persian and Byzantine-Christian custom that Islam adopted. For most of Islam’s history, the veil in its various forms was seen as a sign of distinction and protection for upper-class women. Since the 19th century, the veil has come to represent a more assertive, self-consciously Islamic expression, sometimes in reaction to Western currents – colonialism, modernism, feminism.

Initially in Muhammad’s life, the veil was not an issue. His wives didn’t wear it, nor did he require that other women wear it. As he became more important in his community, and as his wives gained stature, Muhammad began adapting Persian and Byzantine customs. The veil was among those.

Does this justify a burqa ban in the UK? Does this justify banning the burqa in schools or for minor children?

What are the consequences of making the burqa illegal?

Well, then a woman in public wearing a burqa is committing a crime by just walking down the street. If the police see her committing that crime, they have the right to stop her, question her, demand she remove part of her clothing, caution her.

The justification for giving the police power to harass women is supposedly that some women – out of the tiny number who do wear the full abaya in the UK – may not be doing so out of free choice but because their family or their husbands are making them cover themselves completely.

In some instances this is probably true. How on earth will giving the police the power to harass them help? If a man is so lost to humanity that he thinks it appropriate to force his wife or his daughters to cover up when they’re outside the house, his family certainly need help: and congratulations, with the burqa ban you have taught them that the state is their enemy, that the police will speak to them only to harass them.

What about children?

There are three main reasons why a girl might be wearing a burqa to school, covering her face completely, of which the main one in the UK is fairly obvious.

The first and main reason: she wants to.

For whatever reason. Maybe because it annoys her parents: maybe because it pleases her parents: maybe because she hopes it will please the imam at the mosque that she has a massive crush on: maybe because a woman she admires and respects is wearing a burqa and she wants to do like her; maybe because it annoys her teachers: maybe she feels that she is standing up for her faith: maybe she’s read about yet another white man patronisingly explaining that Muslim women don’t ever choose to wear the veil and the racist and sexist bigotry annoyed her (never underestimate the power of a teenage feminist’s annoyance).

For whatever reason. Maybe because it annoys her parents: maybe because it pleases her parents: maybe because she hopes it will please the imam at the mosque that she has a massive crush on: maybe because a woman she admires and respects is wearing a burqa and she wants to do like her; maybe because it annoys her teachers: maybe she feels that she is standing up for her faith: maybe she’s read about yet another white man patronisingly explaining that Muslim women don’t ever choose to wear the veil and the racist and sexist bigotry annoyed her (never underestimate the power of a teenage feminist’s annoyance).

A subset of the main reason: she wants to because she’s been getting sexually harassed and she’s absorbed the cultural message that this is her fault because of what she’s wearing and she thinks wearing a burqa might stop it. She’s wrong, but for any sake, dealing with the creeps who think it fun to sexually harass girls and women is not accomplished by harassing a girl about what she’s chosen to wear.

There is nothing that the police or the government should be doing to stop a girl wearing what she wants to wear. I cannot believe I even have to write that sentence.

It is the responsibility of a school or a college or a university to ensure that their students do not harass any other student for wearing what she wants to wear. It is the exact reverse of responsible behaviour to set up a situation where the bullies are empowered by the school to harass a girl for what she’s wearing.

The second reason: her family and all her community are telling her she must. Her friends at college all wear burqas and to fit in with them she’s going to. This is not good. But it’s also not going to be helped by enforcing a ban by police or courts or college regulations. A student who doesn’t want to wear a burqa and who feels she must because she is under the authority of her parents and they say she must, needs to be empowered by her education to leave home and get out from under her parents’ authority: ensuring her parents have a reason to ban her from further education or that she associates going to school with getting bullied by the teachers for wearing a burqa – isn’t going to help.

You might ask (as tabloids have) what about Muslim schools? The recent Metro story mentions a non-Muslim teacher objecting to wearing the headscarf, and claiming that girls are made to sit at the back of the classroom.

I don’t support any religious school getting state funding.

But, the story seems to be a bit of distortion (never trust the Metro with facts). According to the school itself, the women teachers are required by contract to wear hijab as part of the school dress code, and always have been.

In Primary, boys and girls have never been segregated either inside or outside the classroom. In Secondary, girls are seated as a group, either at one side of the classroom, or alternately at the front or the back of the room, swapping over from time to time. Our intention is to respect both genders equally. These seating arrangements have been determined purely by practicalities such as the size of the classroom.

I don’t agree with religious schools getting state funding. But if Catholic and Protestant schools are allowed to get state funding, then there’s no case for specifically banning a Muslim school.

If a girl is being made to wear a niqab or a burqa to school by her parents when she doesn’t want to, and she is too afraid of her parents to uncover when she’s out of their sight, how is it going to help her if she cannot go to the police or to her teachers for help because the police will arrest her and the school have taught her she’s their target for bullying?

The third reason: she’s recently from a country where girls and women are required to wear the burqa, where this is policed by the state and by men who claim it’s “women’s honour”: and as a direct result she feels she must, she won’t feel comfortable if she doesn’t. Banning the burqa by law or by school fiat isn’t going to help this third group either.

The UK should be a country where a woman gets to wear whatever she wants and not be harassed for doing so.

18th January, at Lifting the Veil: An open letter to Yasmin Alibhai-Brown: like it or not, the niqab ban is racist

“The UK should be a country where a woman gets to wear whatever she wants and not be harassed for doing so.”

Quite right. France has introduced such a ban, and it has only led to trouble: e.g. just up the road from us in Trignac (a small town) http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/7735607/France-has-first-burka-rage-incident.html

Of course, in desert conditions, where sandstorms are an ever present risk, such clothing designs are not entirely without logic, but there’s really no need for it in northern Europe. Those northern Europeans that have taken up the burqa, are, in my experience, akin to punk rockers enjoying the in-yer-face shock value of an inescapable visual presentation of political values. In these circumstances, a government ban will only increase its popularity among that section of the population who enjoys a bit of martyrdom in the face of state oppression: gentle interpersonal deprecation of the habit at grassroots level is more likely to be effective.